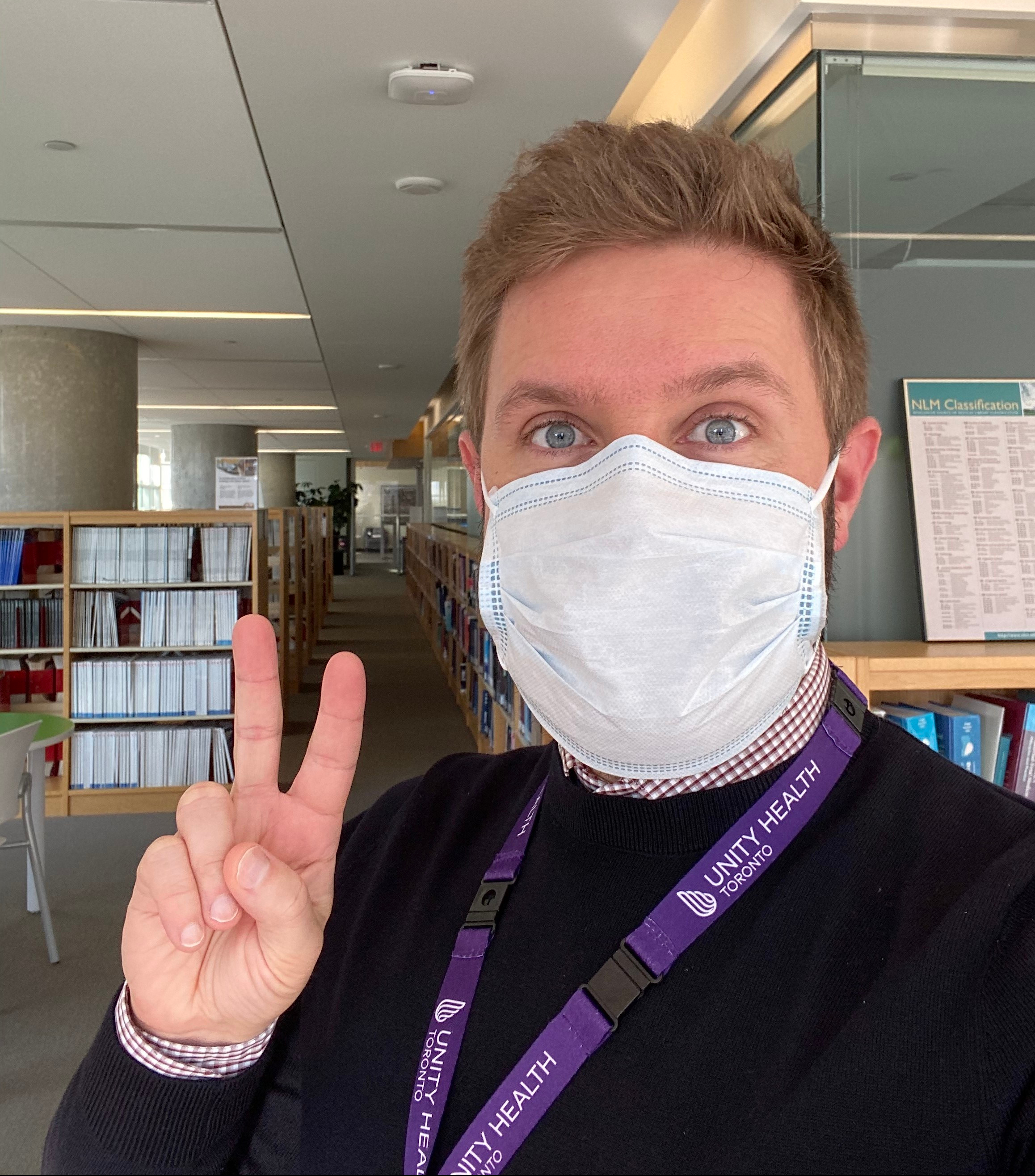

My first full-year as a people leader and department manager was with a hospital/health system during a global pandemic. It was a year chock-full of learning experiences: sometimes through failing or getting it wrong, and others by realizing when I should (and that I can) trust my gut. In my role, I lead a team of eight information professionals (librarians, library technicians, and an archivist) at a multi-site academic teaching hospital network in Toronto. In April 2020 I wrote about my job and my team’s early pandemic activities, and for me at the time, writing about those experiences was a reflective and grounding practice to help gather and focus my thoughts on what I was going through. Like many other department managers in my organization, much of my leadership in the last year was an exercise in “flying blind”; making decisions with the information and best available evidence at the time, and navigating through uncertainty while supporting my team. I led with purposeful intentions of working closely with individuals on my team to check-in on their wellness, support them in resolving individual remote work challenges (e.g. technology, time-management, communication, balancing work and childcare, etc.), all while ensuring and maintaining the Library’s service outputs and deliverables. In 2020 as a team, we accomplished a lot, and I’m extremely proud of the tremendous creative problem-solving, nimbleness for pivoting everything we do to a virtual environment, the volume of new and high-quality services deliverable, plus their collaboration, teamwork, and support for one another while working physically apart. However, things with me (e.g. my own self-organization, work/life balance, wellness, mental and physical health) took a backseat (and I’m talking old-school station wagon all-the-way-in-the-back, rear-facing backseat). Thanks to a lengthy three-week break from work over the December 2020 holidays, I had some distance from my job and seized the opportunity to look back on my first year of management and leadership with a clear(er) mind.

With time and hindsight to reflect on my first year in management and leadership, I want to share five things I read, learned, heard, and self-discovered which resonated with me that I’m adopting into my practice as a leader in 2021 (and beyond).

1. Model the behaviours you want to see from your team

A major lesson I learned as a new manager and leader throughout the pandemic is to make sure I’m modeling the behaviour I champion, exhort, and expect from my team. In mid-March 2020 when all non-essential hospital teams began working remotely for our first lockdown, I communicated and acknowledgment to my team that the circumstances were strange and different, incredibly surreal, new, scary, challenging, abnormal, and unlike anything we’ve experienced before. I shared that I did not expect the same level of productivity from the team – times were stressful enough as they were – and, that the most important things were to take care of your mental and physical health, be kind to yourselves, communicate when you need support, be patient, take breaks, do your best, and we’d take things one day at a time. Makes heaps of sense, right? I thought so too! Except, I wasn’t doing any of these things. I was telling my team one thing (praising a new mindset of slowing down, being kind to yourself, thinking of productivity differently, etc.) while I went into overdrive with work. Because I was so new at having the responsibilities of my role (i.e. managing team performance, overseeing operational spaces at three hospitals, ensuring the budget and fiscal year-end were closed properly by March 31, operationalizing library strategic objectives, attending hospital senior leadership meetings to obtain information I needed to share with my team, etc.), I was not following my own advice. Somehow it didn’t register with me that I should also practice these basic principles, and wrongly, in retrospect, it seemed or felt to me that it was my duty and responsibility as a manager to work even harder under the circumstances. I would work on the weekends, and I dutifully continued working from on-site at the hospitals, mostly (I believe now) due to an unfounded concern that, as a manager, I would be needed to respond to something urgent at any moment.

Unconsciously I felt a sense of vocational awe, where my duty as a “fearless leader” was to be everything to everyone in these pandemic times, and to work even harder than normal. Somehow I didn’t recognize it (at all) at the time, but looking back I see how it sent the wrong message to my team. There would be times I’d see members of my team working too much, exhibiting great anxiety and stress over workload, and expressing scrutiny towards me for being on-site, and I would feel confused and wounded that they weren’t heeding my advice. I didn’t recognize my own hypocrisy, that I wasn’t setting the right example of the behaviour I expected from my team. I was able to speak about these experiences and my lessons learned at the 2021 OLA Super Conference in panel sessions about leadership in turbulent times and providing information services in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and I think talking openly and sharing these missteps have helped me understand myself better, and hopefully can help others feel more comfortable expressing these challenges as well. Overall, it would be great to foster a culture of openness among leaders with these topics/issues.

In 2021, I’ve embraced a new approach to work that actively values work/life balance: I don’t work or send emails all hours of the evening or work on the weekends, I communicate openly to my team when I’m taking a break in the middle of the day, I take vacation days often and encourage my team to do the same, and I’ve worked entirely remotely (just like them) with great success. I’m a work in progress, but so far, so good.

2. Recognize (and learn from) burnout and impaired wellness

These days we talk a lot about burnout. “Burnout” is defined by the World Health Organization as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: 1) feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; 2) increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and 3) reduced professional efficacy.” Burnout isn’t just a description for feeling exhaustion from work, there are actually scales of burnout, which define and characterize the symptoms and factors which contribute to ultimate burnout. Health professionals and educators often use the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) to help self-assess their stage of burnout.

My experiences in 2020 with burnout and impaired wellness probably aren’t unique from yours or others in our society. Eventually I became exhausted from working too much and too hard, began losing interest in aspects of my work that I typically enjoyed, developed a negative and cynical attitude toward new projects or work requests, felt depressed, anxious and overwhelmed, and felt just completely over it. Not to mention I secretly picked up smoking again, and (not-so-secretly) gained 19 pounds (the other “COVID-19“). Not great!

While I don’t think many folks would encourage anyone to experience burnout, there is growing literature to suggest that burnout and impaired wellness aren’t such bad things if/when you can harness reflection for the experience and how you responded to it, and focus on learning, building resilience, and growing from the incident. I recently heard a thought-provoking consideration of the ignored value of impaired wellness and burnout, discussed in an interview with Will Bynum on the Medical Education Podcast in the episode “Why impaired wellness may be inevitable in medicine, and why that may not be a bad thing“. In the episode, Bynum suggests how we are “undervaluing the potential growth and resilience that can be developed through engaging with those experiences”, and shares from personal experience that “each time I’ve dealt with [burnout] I’ve gotten better at identifying it, kicking in some coping mechanisms, and recovering from it.” I was inspired by the mindset of seeing burnout with a “silver lining” point of view, and it made me think differently about my own experiences with impaired wellness and burnout. To prepare myself for the future, I’m reflecting on my instances of impaired wellness and asking myself the questions below to help develop resilience and learn from the experiences I had:

- What characteristics did you recognize that indicated you were feeling burnout?

- How did your behaviour or attitudes change?

- What will you do differently next time if/when you identify feeling these ways?

- What strategies will you use to cope differently or to mitigate scenarios within your control?

3. (Re)Consider the format of every meeting (or even cancel the meeting)

In the early days of the pandemic I heard from many folks on my team that they were lonely and missed the human connections at work. I was concerned about their feelings of isolation and despondency and I wanted to ensure they retained a sense of connection during the abrupt and unfamiliar switch to remote work. As a result, we met as a team and held individual update meetings more regularly through Zoom, and were in constant contact using Slack. Meeting so often (and on Zoom) made a lot of sense in the beginning, and for some individuals it continued to make sense throughout the year. But, after a while, it felt like we were meeting an awful lot, and our days became full of back to back Zoom meetings. We were also very busy, and I routinely questioned to myself if we truly needed to be meeting at all (especially for the default 1-hour which so many meetings are scheduled).

For 2021 I’ve adopted a new approach for meetings with members of my team. I try to reflect on the purpose, the need, the format and length of each meeting, and in advance I’ll check-in with the person I’m meeting to ask if they have a preference for the meeting format. If the purpose or need for the meeting aren’t pressing or urgent, I’ll propose we cancel or reschedule the meeting. Here’s my guiding decision-framework:

- Do you need to hold the meeting you’ve organized?

– Yes/No

– Unsure? Ask the person/people you’re meeting - For each meeting, determine the best or most appropriate format to meet:

– Zoom: Use if something must be shared and discussed visually; there are 3 or more participants; or you want face-to-face time

– Phone: Use if there is nothing to share or discuss visually; there are 2 participants in total; it’s intended to be a short conversation; either of the meeting participants do not wish to be on videoconference for any reason, or it’s not a good time for videoconference due to nearby distractions like children, partner or roommate also has a meeting, etc.

– Email: Could this meeting be an email? Consider sending an email instead of meeting if the purpose of the meeting is simply information sharing without any discussion or input.

– Slack: If there’s not a lot of need/purpose for a meeting, and you’re checking-in with the person about a) whether you need to meet, or b) the preferred format, ask them if they’d like to merely have a chat on Slack about the meeting topic. Avoid phone or videoconference altogether! - Length of the meeting:

– Not all meetings need to be an hour! Be brave, schedule a meeting for 15, 30, or 45 minutes.

– If your meeting needs to be an hour, be mindful to schedule gaps allowing for short breaks between meetings (i.e. start the meeting at 9:10 instead of 9:00 on the dot).

4. Be authentic and brave, show you’re human too

As a manager and people leader, I’m learning to recognize and appreciate the importance of showing vulnerability, communicating honestly (about my wellness and my needs, etc.), the benefits of being transparent about workload and stressors, and ultimately showing my authentic self to my team and colleagues. I suppose I’m talking about the idea of bringing your whole self to work. For some people (and perhaps for more people than I’m aware), this is hard work! I’ve been mindful of this ever since I started working, and have always struggled with being my whole self in a work context. I think as a gay man I’ve had to work-through and unpack the shame associated with being gay, and it’s impacted how I behave and communicate in a “professional” environment. There’s a whole other blog post about this in my head somewhere, but I’ll summarize by saying that for a very long time I’ve had my guard-up in professional settings in an effort to hide or conceal my authentic self from fear of homophobia or discrimination.

However, what I have learned from 2020 and in my current work setting, with my present colleagues, and in my leadership and management role, is that showing myself and being authentic actually does make things better, and I’m encouraged to do it more. Being vulnerable, open, and honest sets a positive example for your team and fosters a culture of openness, and encourages or gives permission to members of your team to do the same. I underestimate the influence I have on my team, and I see now that when I’m open, vulnerable, and honest, it’s not only appreciated, but I see others mirroring those behaviour too.

5. “Wellness” isn’t just a buzzword

The three weeks of vacation I took in December 2020 were a life-saver. I needed that time away from my job more than thought. It helped to change my outlook, improved my mood, and helped me see my job in a more positive way. I used this time off to re-focus on things I’d been missing that bring me joy, like reading for pleasure, cooking, going for walks, and watching a ton of bad TV. In a nutshell, I learned I need to incorporate the following into my routine: take breaks, breathe deeply, read more, and get daily exercise (and I mean something as easy as going for a walk).

The lesson I learned is that no matter how busy I get, I need to prioritize wellness and make time to get what I need to recharge. It will always pay-off and help a headspace that is stressed-out, anxious, or overwhelmed. For me, “recharging” can look like taking three minutes to complete a breathing exercise (here’s a great .GIF for guided box breathing, and another one for simple deep-breathing), going for a short (or long) walk/getting some fresh air, or changing a routine to incorporate things that bring opportunities for reflection, relaxation and calm (e.g. reading, reflective practices/exercises) because ultimately it will help you feel better.

So, this concludes my very long-winded list of five things I learned in my first full-year of management and people-leadership in 2020 during the pandemic. I hope there is something you took away that may help you in your life/work, and that some of the experiences I shared resonated or were validating for you.